The recent passage of the finance bill in Kenya has been a deeply controversial and tragic affair, raising critical questions about governance, public participation, and the value of human life in the face of political decisions. Were unrest and death necessary catalysts for the government’s eventual decision to withdraw the finance bill?”

Public participation: JUST A FORMALITY

Public participation is a cornerstone of democratic governance, enshrined in our constitution. It ensures that citizens have a voice in the legislative process, particularly in matters that directly impact their lives. In the case of the finance bill, public participation was one of the critical stages before its presentation to parliament. However, despite significant public opposition, the government representatives appeared to dismiss these concerns, with some exhibiting arrogance rather than empathy. The dismissive attitude of government representatives during the public participation phase suggests that this process may have been treated more as a formality than a genuine attempt to engage with the populace. The public’s distrust in their representatives grew, leading to the decision to protest outside parliament on June 26th, hoping to prevent the bill’s passage.

As frustration mounted, the protests turned violent. Demonstrators breached parliament, and tragically, some lost their lives. Others were abducted or arrested in the chaos. It was only after these deaths that the President decided to withdraw the bill. This sequence of events raises a profoundly disturbing question: Did people have to die for the government to reconsider its stance?

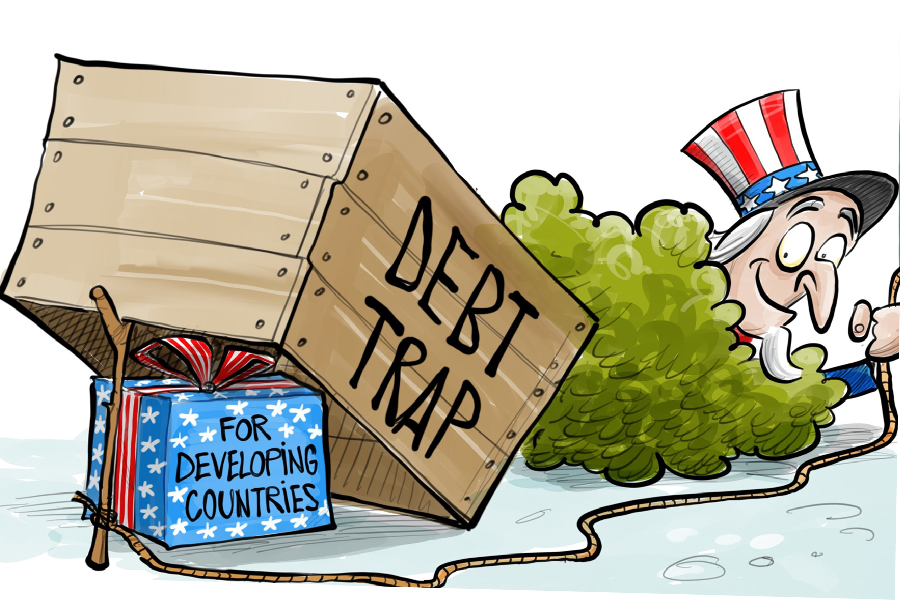

What was so important in the finance bill that it warranted such a heavy toll on human life? The bill included measures like new taxes, increased VAT, higher fuel taxes, and taxes on digital transactions—policies that many believed would exacerbate the financial burden on already struggling citizens. While the government might have argued these measures were necessary for economic stability and development, the public saw them as unjust and harmful The deaths during the protests highlight a severe disconnect between the government and its people. The tragedy suggests that the government might have underestimated the public’s grievances or chose to ignore them entirely. This raises further questions about whether the government truly understands the needs and desires of its citizens, or if it prioritizes its agenda over the well-being of the people it serves.